Kendrick Leong

March 14, 2020 saw the earliest declaration of cherry blossom season in Tokyo on record. But while this symbolic start of spring may fluctuate year to year – a week earlier in 2020, and from March 21 in 2021 – other spring starts pepper the Japanese calendar in March and April. The start of the academic school year and corporate onboarding of new recruits accompany the blossoming of sakura trees. And data from the Report on Internal Migration in Japan, published by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications’ Statistics Bureau, suggests that these starts may be reflected in internal migration patterns.

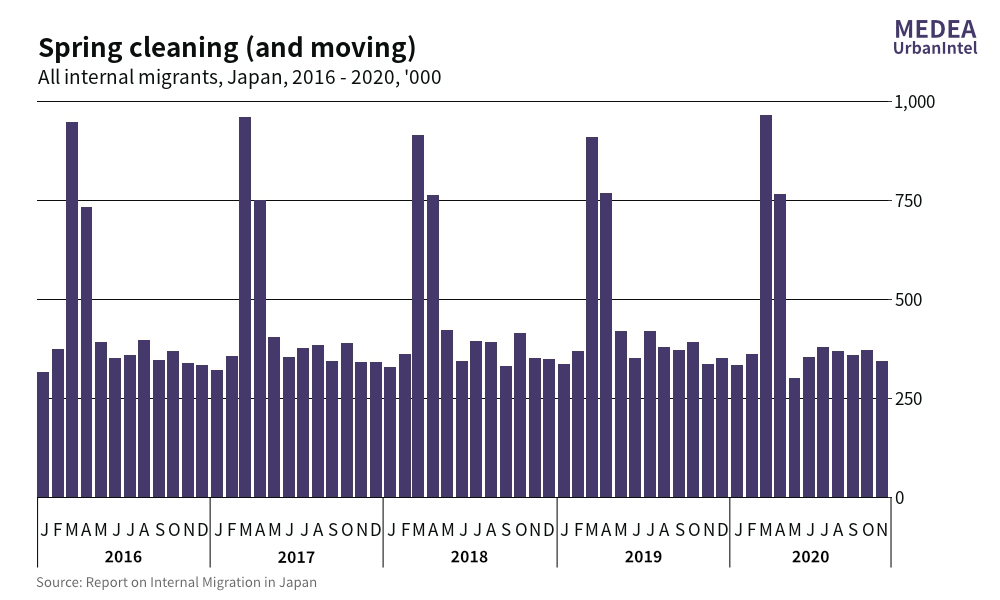

Internal migration is calculated by the Statistics Bureau by tracking legally required reports to municipal officials whenever a Japan resident moves between municipalities. What stands out is the spike in internal migrants – including those moving between prefectures as well as those moving within prefectures – in March and April of 2020. Our first question here, as with countless other exploratory data analyses about 2020, is naturally, but unfortunately: Is this pandemic related?

Let us reference that the first COVID-19 case reported in Japan was in January; timelines may line up here. Could we be seeing the rumored urban exodus debunked elsewhere? To find out, we bring in data for the past five years, starting in 2016.

What we see in the five-year data is similar spikes in March and April, consistently, every year. And these spikes are large – nearly 1.5 million Japanese residents move between municipalities in these spring months. Let us also reference that the first state of emergency in response to COVID-19 was declared on April 7, 2020, for Tokyo and later expanded to the entire nation. This state of emergency lasted until May 25, 2020, bookending the spring migration spikes.

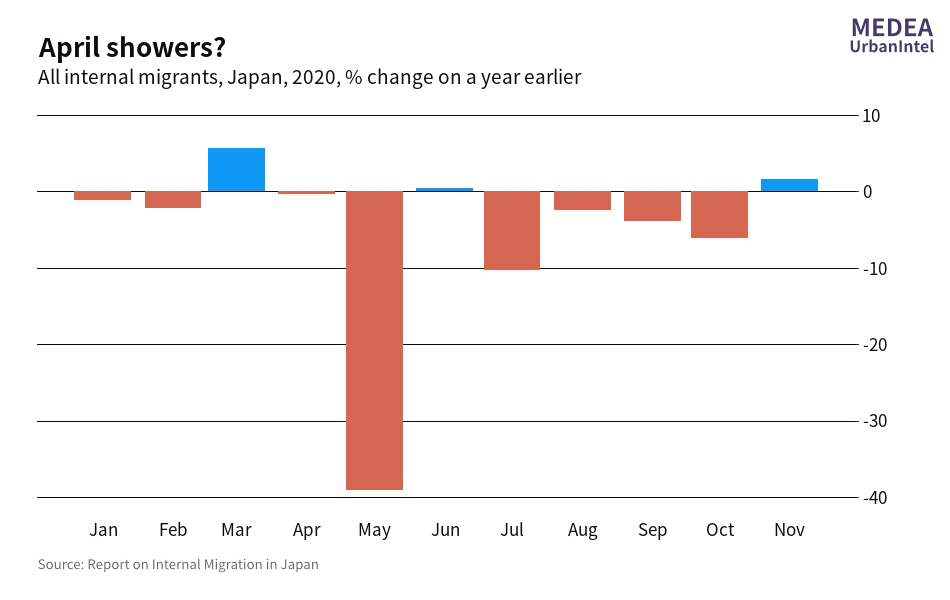

The strength of the spring migration spike may have weathered the state of emergency. In April 2020, nearly 376,000 residents moved within their prefecture, and another 388,000 residents moved to a new prefecture, for a total of around 764,000 internal migrants nationwide. However, it is apparent that the state of emergency heavily impacted internal migration for May of 2020.

Internal migration tanked for May 2020, recording a forty percent decrease over 2019 numbers, and coming out to about 120,000 fewer individuals moving across municipalities. Some of these moves may have been postponed to June, with the lifting of the state of emergency. However, internal migration continued to fall short of 2019 numbers for the summer months and into the early autumn. A small uptick in November 2020, the latest month for which data is available, could represent moves that were postponed until the winter.

We could entertain any number of explanatory hypotheses: fewer work-related moves, most interestingly those of “business bachelors,” often young males that are dispatched to distant corporate posts; the move of some university semesters online; and the growing popularity of remote work (although not yet widely adopted). We hope to further investigate some of these topics in future blog posts.

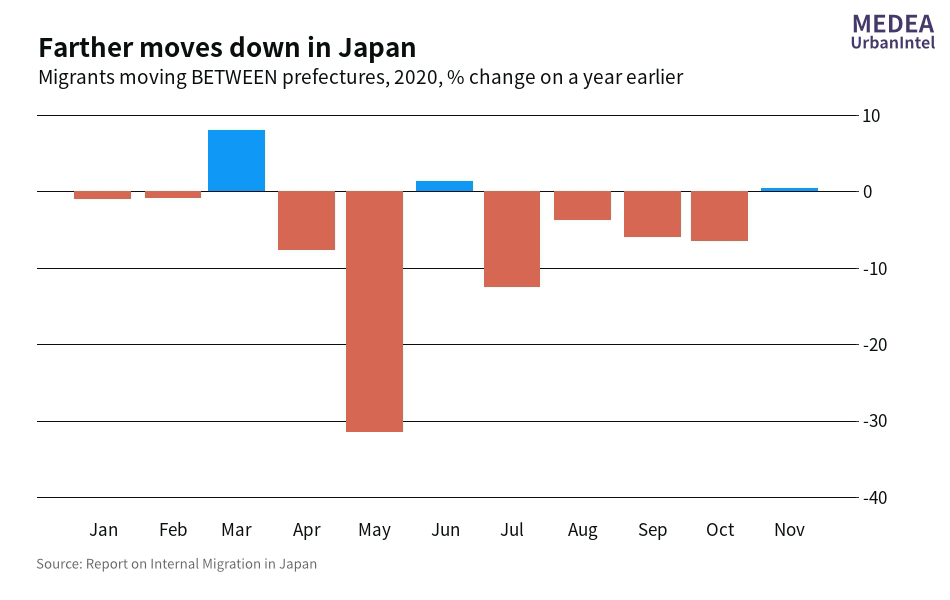

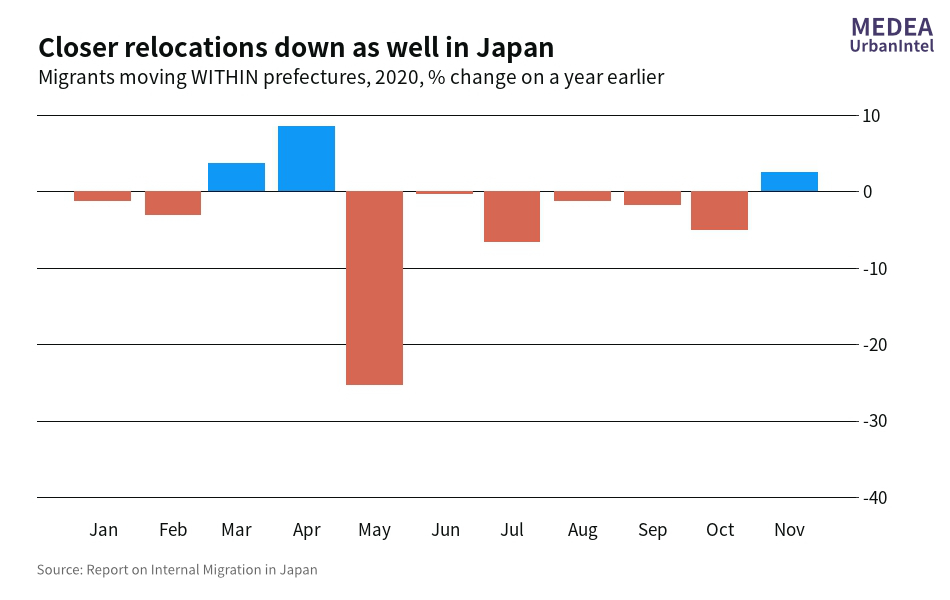

Working with the Report on Internal Migration in Japan data, we can further explore some of the trends within the larger decline in migration nationwide in 2020. Inter-prefectural migrations – that is, across prefecture lines – show a decrease in April 2020 compared to a year earlier. This may suggest some reluctance for big moves amidst the national state of emergency.

Both migrations across and within prefectures mirror larger trends in internal migration for Japan as a whole. In intra-prefectural migrations – those within prefecture lines – we see a growth over 2019 numbers in April. This increase in year-on-year intra-prefectural migrations, combined with April decreases in inter-prefectural migrations, creates a wash on the national level, compared to 2019. In general, the migration decreases seen over the summer and autumn are less pronounced amongst migrations within the prefecture.

As we tinker with the Report on Internal Migration data, we can revisit some of the points brought up earlier. The March and April 2020 migration spikes are cyclical – we have seen these spikes yearly in the five-year data. As far as the nationwide state of emergency goes, it did not significantly impact the March or April migration spikes; however, its effects can be seen in the May drop, as well as consistent year-on-year decreases through the summer and autumn. It may very well be that the signs of spring in Japan – cherry blossoms, college entrance ceremonies, corporate initiations, and now, as we see, internal migration – still held in 2020.

In the next part of this series on migration we will zoom in on more granular data from the Report on Internal Migration. We have looked at when people are moving, we will next turn to where people are moving. We will also begin to examine migration trends specifically for the Tokyo metropolitan area.