Kendrick Leong

It’s the crunch of asphalt under your feet after a long drive. It’s the cold mountain air after three hours of recirculated car heating. It’s the coffee milk enjoyed on a picnic bench. Beyond providing the “rest” in rest stops, Japan’s numerous michi no eki, (lit. “roadside stations”), serve a peculiar niche fusing comfort station, farmer’s market, and civic space.

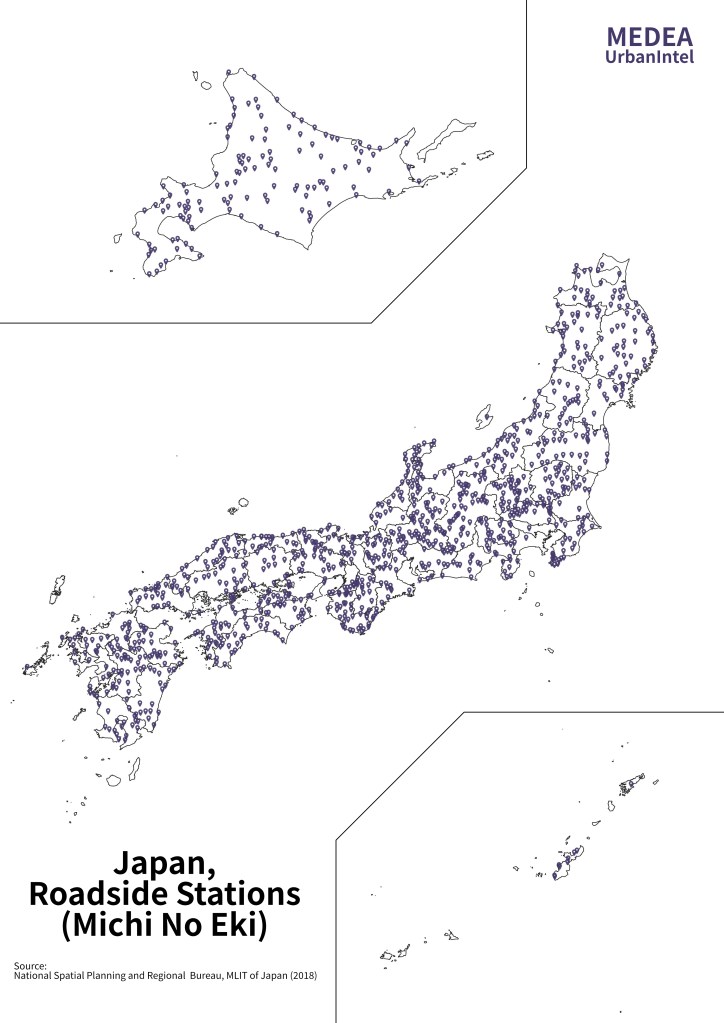

The concept of a highway rest stop is rather simple: somewhere along an expressway to park, refuel (both our stomachs and the gas tank!) and recharge before the next leg of a car journey. But the michi no eki take this concept one step further by showcasing local goods and offering tourism information about the area. These pivots to regional revitalization, with michi no eki as important conduits of community empowerment, have attracted attention from the Japan central government as one strategy to attenuate the effects of dwindling rural populations.

There has been a heartwarming amount written about michi no eki in English, from their catalytic impact on regional revitalization to the individual ingenuity of their operators and the differences between michi no eki and other types of rest areas. Several trends are apparent:

- Michi no eki form the skeleton of a decentralized tourism network, giving local entrepreneurs, farmers, and boosters a platform to showcase regional specialties.

- Michi no eki are essentially in an arms race to attract travelers, with many boasting hot springs (onsen) on-site and a growing provision of lodging, cultural experiences, and unique attractions.

- However, the extent that regional revitalization can pivot off of the flexibility of michi no eki facilities (in offering unique attractions, etc.) may be predicated on, essentially, rural tourism – drawing in guests through regional specialties and experiences (a “can’t get anywhere else” factor).

To the last point, rural tourism is great for promoting regional revitalization (in terms of money injected into the local community and all that). There are also emerging trends that point to regional revitalization beyond mere monetary transactions – that there are sustainable ways to attract interest in rural areas in addition to selling local produce or value-added goods.

One point of pivot could be the michi no eki as civic space (written about extensively in the World Bank’s in-depth exploration of michi no eki), wherein the michi no eki serves as a focal point for knowledge creation (and spillover!) and public services. There are numerous instances where a michi no eki will also serve as a training center, education facility, meeting space, or convention hall, open not only to highway users but also accessible to residents via local roads.

Zoom in: Ten-ei

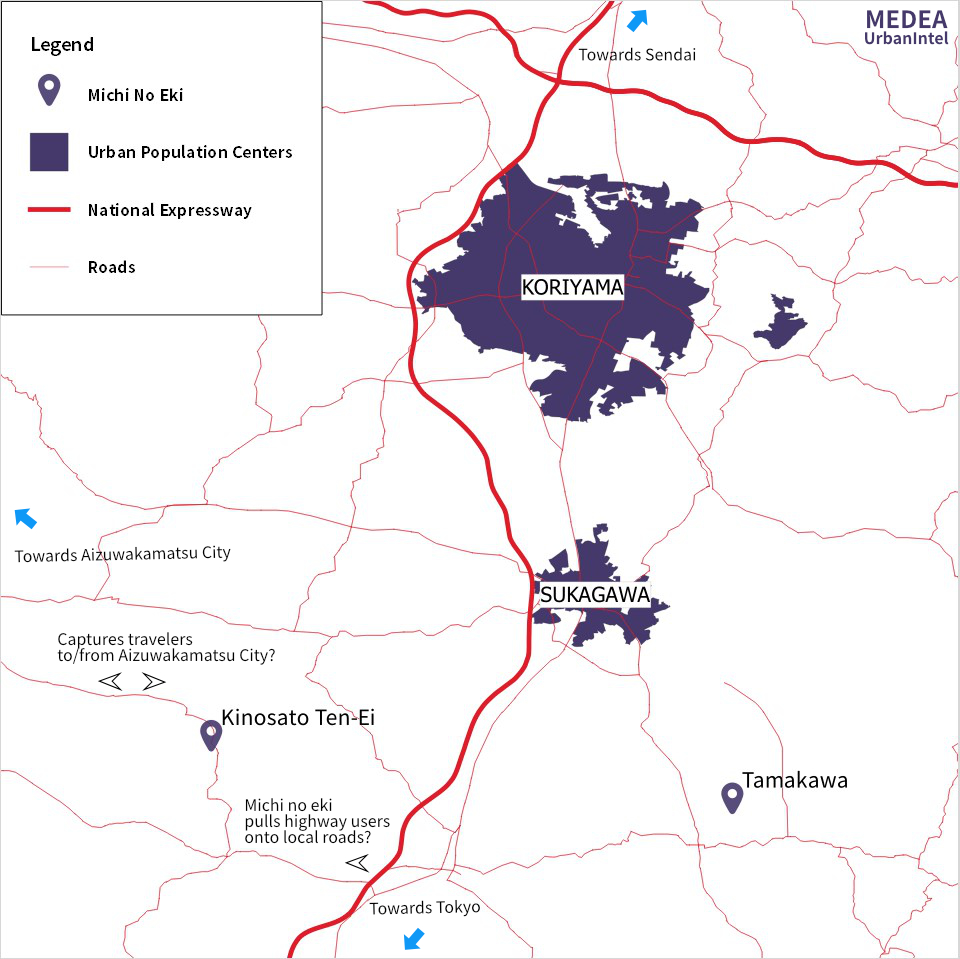

For many, their first experience in a rural area may be a michi no eki. It was for me – our pit stop on the way to a college club event in Ten-ei village was the area’s michi no eki, Kinosato Ten-ei. Ten-ei village (official site, Japanese), a village true to its name, is a picturesque hamlet in inland Fukushima Prefecture, population skirting 5,000, formed from the merging of several other villages in the mid-20th century. Like many other places around the country, Ten-ei’s population has steadily declined as youngsters leave for larger cities for school or work.

Lacking any passenger railway connections, the main access to Ten-ei is by car, necessitating a rest stop like Kinosato Ten-ei. If there is truly an amenities arms race amongst michi no eki (see: theme park-scale michi no eki such as Kawaba Denen Plaza in Gunma Prefecture) then frankly Kinosato Ten-ei cannot compete. However, it is these smaller michi no eki that have the potential to connect local farmers and entrepreneurs to the vitality of the national expressway – whether that is to those with purpose-driven trips to the area (as we did on the way to Ten-ei village) or to those passing through (see diagram).

The flow is simple: these michi no eki provide parking, and a small shop or food stand. The site showcases local specialties (yams and rice at Ten-ei) or educate about the area (now we know what a yacón is and how much is grown in Ten-ei; it can also serve as a delicious substitute for many root-based dishes!). Then, the calculus for effectiveness for smaller michi no eki such as Kinosato Ten-ei is how much of the nearby expressway’s traffic it can divert.

For many others, the amenities arms race is one strategy – make the station a destination in and of itself. For Kinosato Ten-ei it may be promising for the michi no eki to act as an innovation hub for testing out regional revitalization strategies devised by the area’s residents. As volunteer teachers we tasked our pupils in Ten-ei village with this endeavor and heard many proposals brimming with energy and regional pride – from guided ghost tours to value-added products. There is still a lot to explore about michi no eki, but the flexibility of programming these spaces leaves many doors open.

Resources

I used several GIS shapefiles to put together the maps in this blog post. You can access them (and do your own mapping!) here:

- Japan – Subnational Administrative Boundaries, 2019 (UN OCHA Humanitarian Data Exchange “HDX”)

- National Expressways, 2019 (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism “MLIT”)

- Population Centers, 2015 (Japan MLIT)

- Major Roads, 1995 (Japan MLIT)

- Michi No Eki, 2018 (Japan MLIT)

I also used a modified Marker icon created by Fatkhul Karim for The Noun Project to demarcate the michi no eki.